Unlike adult cancers, which are often linked to lifestyle and environmental risk factors, the cause of many childhood cancers remains unknown. While advances in research and care have greatly improved chances of survival, cancer remains the second-leading cause of non-accidental death among children in Canada.

“Childhood cancers are unique in that they not only grow differently than adult cancers, but they respond to treatments differently too,” says Dr. James Lim, an investigator at the Michael Cuccione Childhood Cancer Research Program at BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute (BCCHR) and an associate professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of British Columbia (UBC) Faculty of Medicine.

Right now, fewer cancer drugs are considered safe for children, so when a conventional treatment, like chemotherapy fails, or if the cancer returns, the road ahead for children and their families can seem daunting.

But what if it was possible to bring new hope by pinpointing which cancer treatments have the best chance of success before they are even administered to a child?

In the first laboratory of its kind in Canada, Dr. Lim and his colleagues are tackling that very question — using a surprising, but powerful research tool.

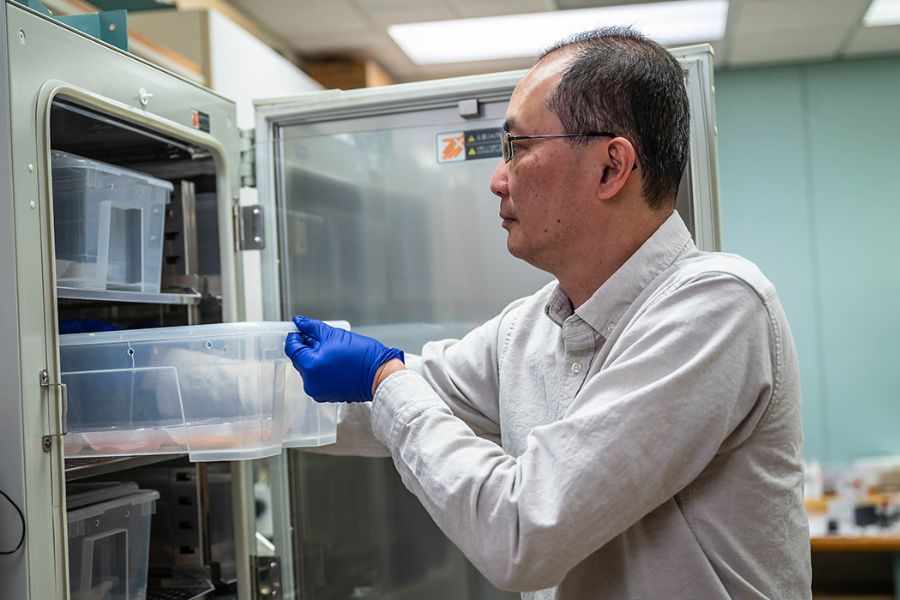

“In my research lab, we’re using chicken eggs as a host model to grow the child’s tumour in a petri dish,” says Dr. Lim, an expert on drug resistance in pediatric cancers.

“We’re then able to test different drugs targeted to the unique properties and weaknesses of each tumour, and see how the cancer cells will respond.”

By pre-testing treatment options in the safety of a laboratory setting, Dr. Lim and his team are helping pinpoint what drugs work well, understand why some drugs fail, and ultimately offer treatment options with the highest chance of success for children battling hard-to-treat or recurring cancers.

While the chicken egg model (technically known as the chorioallantoic membrane or CAM) is not new to pre-clinical cancer research, Dr. Lim and his colleagues are the first scientists in Canada to use the model in the field of pediatric cancer research.

“The primary advantage of using the chicken egg is that it’s a rapid model,” says Dr. Lim. “It takes just one to two weeks to grow a tumour from the time of the initial biopsy — this represents a dramatic drop from the current standard of three to six months using other models.”

Dr. Lim’s game-changing work is part of a much bigger pediatric precision oncology initiative, known as the Better Responses through Avatars and Evidence (or BRAvE).

Comprised of a passionate team of researchers based at BCCHR, the BRAvE team is using cutting-edge mass spectrometry and genome sequencing technologies to determine the unique molecular makeup of childhood cancer tumours – all in an effort to find treatment options with the highest chance of success and the fewest side effects.

The team’s findings are then shared with the child’s health-care team — helping to guide next steps, inform treatment plans, and ultimately bring new hope to children who are faced with a cancer diagnosis and their families.

According to Dr. Lim, one of the biggest challenges in treating pediatric cancer currently is that far fewer cancer drugs are approved for children.

“Oftentimes, different tissues are affected in childhood cancer and fewer cancer drugs are considered safe for children,” says Dr. Lim.

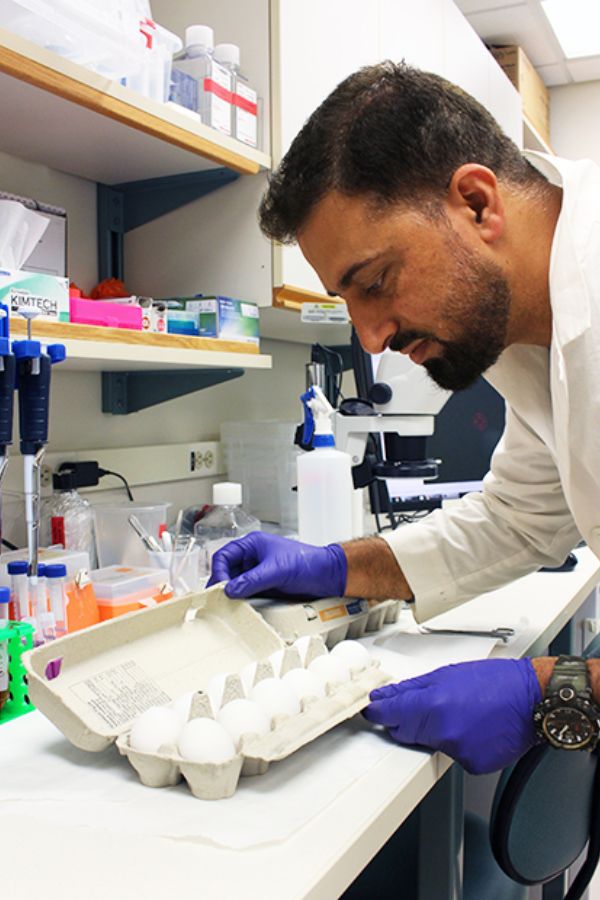

Which is why Dr. Lim and his colleagues at BRAvE, including PhD candidate Tariq Bhat, are exploring new avenues, even investigating and testing already-approved drugs used to treat other childhood diseases and conditions altogether.

“We’re exploring all possibilities,” says Dr. Lim. “The best-case scenario is when we find an existing drug that has already been approved for use in children and can be repurposed in the fight against cancer.”

While it’s early days, Dr. Lim is hopeful that his work and that of the broader BRAvE initiative will help to fuel a revolution in pediatric cancer research and care – not only here in B.C., but across Canada.

“Until recently, treating pediatric cancer has basically been a one-size-fits-all approach,” says Dr. Lim.

“We now have an opportunity before us to embrace these exciting advances in precision medicine research to help inform treatment and save lives.”

Credit: UBC Faculty of Medicine