Skylar was a great artist who had lots of friends in kindergarten, but she struggled to read the word “cat” and often wrote a few of her letters backwards. She felt different from other kids, so she was keen to participate in a BC Children’s Hospital project to see if her brain was wired differently from those of her classmates, even though it meant undergoing two MRIs when she was eight.

Six years later, she’s participating in a new phase of the project that’s being led by Dr. Deborah Giaschi, BC Children’s Hospital investigator and a professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of British Columbia (UBC).

Dyslexia is the most common learning disability in children

Between one in eight and one in 20 people have dyslexia, a neurodevelopmental disorder that involves difficulty reading and is often associated with problems identifying speech sounds and learning how sounds relate to letters (decoding). Also called a reading disability, dyslexia affects the way the brain processes written language. About 70 to 85 per cent of children who are placed in special education for learning disabilities have dyslexia.

Dyslexia is not connected to IQ, and people with dyslexia tend to be creative, and great problem solvers, but their challenges in reading can make many areas of learning difficult.

Risk factors for dyslexia include a family history of the disorder or other learning disabilities, and individual differences in the parts of the brain that process language.

Using MRI to shed light on dyslexia

Dr. Giaschi wants to better understand dyslexia and how those with this neurodevelopmental condition can best develop their readings skills.

“People who grow up with unremediated reading difficulties are more likely to have fewer job prospects and more psychosocial and mental health challenges.

They are also more likely to end up in prison than people who grew up with normal reading ability,” says Dr. Giaschi.

With the help of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant, Dr. Giaschi and Dr. Linda S. Siegel, emeritus professor in the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology and Special Education at UBC, guided three studies led by then-PhD student Dr. Marita Partanen that focused on the differences between the brains of children with dyslexia and those without, and the differences in the brains of children with dyslexia before and after reading support.

Working with Grade 3 students in the North Vancouver School District, the researchers studied typical readers, children with below-average reading who remained in their regular classroom and received group learning assistance three times a week — as is common in many schools — and children, such as Skylar, who spent three months studying at the district’s Literacy Centre.

They performed MRI scans on the brains of all of the children at the start of the study and three months later. Children in the below-average reader groups received reading support during these three months; children in the typical reader group received regular classroom instruction.

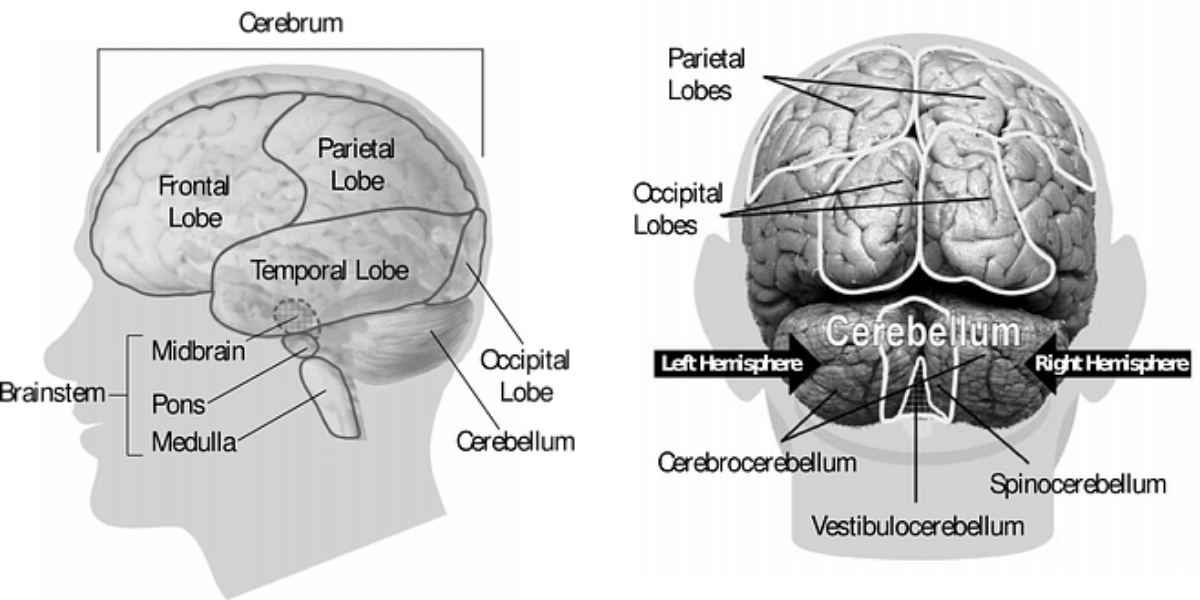

The research team performed four different types of MRI scans on children’s brains to show differences between the brains of those with dyslexia and those without, and differences after the reading interventions. One scan looked at brain structure, a second looked at brain function while reading, a third scanned their brains while they were resting, and a fourth focused on structural connectivity of white matter tracts, which include the projections of nerve cells (axons) surrounded by sheaths (myelin).

Reading interventions improved brain function

Following reading interventions, the researchers used functional MRI to scan children’s brains while they read. They found the children showed improved activation in brain areas associated with reading. The bulk of the improvement was in areas involved in phonological processing, specifically deciding whether two words rhymed.

The investigators also compared the immediate and one-year reading improvement for the three sets of children who participated in the study.

Those who studied at the Literacy Centre showed an improvement in word recognition and decoding fluency immediately after the program and a year later, and significant reading impairments decreased by nearly half at follow-up.

But in both below-average reader groups, a significant gap between their skills and those of the typical readers remained.

Brain differences

Previous studies have established that regions in three different areas of the brain — mostly in the left hemisphere — are activated during reading tasks: the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes.

The brains of children with dyslexia featured more disruption in connectivity between the different parts of the brain related to reading, but the children who showed greater gains in reading after three months of intervention showed an increased connectivity in their right brain hemisphere.

“It looks like their brain is trying to compensate for working differently in the left hemisphere,” Dr. Giaschi says.

The research team is now preparing to analyze functional MRI scans to see which part of the children’s brains are activated while at rest. This is important for examining how regions throughout the brain work together, and it may provide a way to scan even younger children in the future.

Some children with dyslexia have visual deficits, particularly in motion perception, and how this relates to dyslexia remains controversial. The researchers will examine the parts of the brain related to motion perception and how they’re connected to reading regions in the brain.

What this work means to children and their families

Skylar’s mom, Vicki McArthur, said three months at the Literacy Centre “totally improved” her daughter’s reading and writing skills.

“It also gave her more confidence about having dyslexia because it highlighted that she wasn’t alone.

In her school, she was the only one that had dyslexia, and at the Literacy Centre, there were a whole bunch of kids from other schools.”

Skylar also discovered that she and her classmates at the Literacy Centre had different weaknesses and strengths.

“What I liked most is that they were able to help each other,” McArthur adds.

She says her daughter wasn’t worried about having MRIs when she was younger. Skylar hoped participating in research would mean she’d be cured.

But learning her brain worked differently from kids who don’t have dyslexia helped Skylar.

“She finally recognized it isn’t a disease; there isn’t something wrong with her that needs to be cured. It’s just a difference.”

For more information on dyslexia, see:

International Dyslexia Association

Learning Disabilities Association of Vancouver