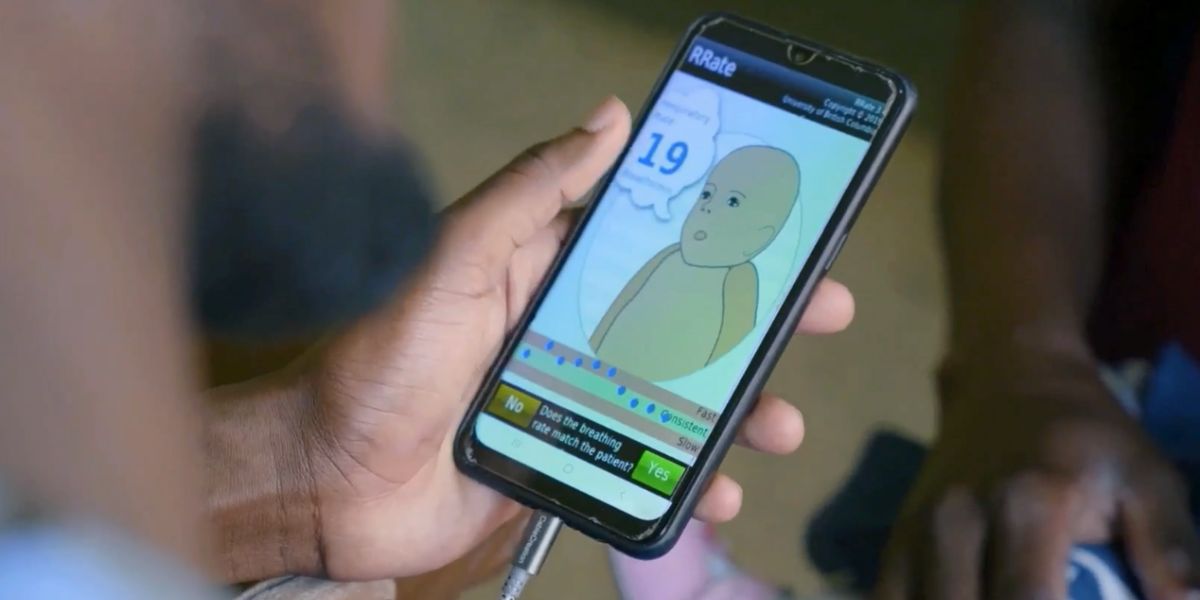

An innovation from BC Children's Hospital Research Institute (BCCHR) could have a positive impact on children worldwide. A team of researchers at the Institute for Global Health (IGH) have developed the RRate app — a mobile application that measures respiratory, or breathing, rate. Frontline nurses in two busy hospitals in Uganda, a partner country of IGH, have successfully used the app to support clinical decision-making. Breathing rate is a key factor to help identify young people with pneumonia, the disease that causes the most deaths in children under the age of five globally. Widespread use of the RRate app in low-resource settings could help reduce the risks of misdiagnosis and save lives.

“We invented, validated, and used this app in clinical studies, and recent data confirms that thousands of children in East Africa are benefiting hugely from it,” says Dr. Mark Ansermino, the co-executive medical director at IGH, an investigator at BCCHR, and a professor in the Department of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology & Therapeutics at the University of British Columbia. The latest research on the RRate app, published in PLOS Global Public Health, investigated its repeatability — if a health-care worker would obtain the same results if they repeatedly measured a child’s breathing rate in a busy environment by using the app.

“There’s evidence that RRate is a better option than devices currently available when caring for restless children,” Dr. Ansermino says.

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs that prevents them from functioning effectively, causing the patient to breathe faster to get enough oxygen. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), children should be treated for pneumonia if fast breathing is present, but fast breathing on its own is not enough to make a diagnosis. In well-resourced health settings, pneumonia is typically confirmed by a chest X-ray, but this exam is not always available, which could lead to a potential misdiagnosis.

In a clinical setting, measuring breathing rate is difficult. “Most often, clinicians will be counting the patients’ breaths assisted by their watches, and they’ll typically count for 15 seconds, then multiply it by four to record the patient’s breaths per minute,” says Dr. Ansermino. In busy hospitals, with many patients waiting for care, even one minute can be a long time. One of the challenges is this method is hard to carry out accurately while the clinician is multitasking, such as looking at their watch and the child. Another is the reduced accuracy of the measurement due to rounding. “If, in 15 seconds, I measured 5.6 breaths and rounded it down to five, I get four times that inaccuracy when I multiplied it by four.”

Inaccurate breathing rates can lead to patients being overtreated or undertreated. Diagnosing a child with pneumonia when they don’t have it can cause issues such as antimicrobial resistance. “All of a sudden, none of the common drugs work because that patient was taking medication unnecessarily,” Dr. Ansermino says. This approach also leads to misuse of resources that might be already limited, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). If, instead, the clinicians fail to diagnose a child with pneumonia and send them home without adequate treatment, they could die.

Available for free download from the app stores, RRate is an easy-to-use option for health-care workers to reliably measure breathing rate. The only requirement is to have a smartphone with a touchscreen, which has become more common, including in LMICs. “The app even runs on old smartphones,” says Dustin Dunsmuir, the IGH Technical Lead, who was responsible for coding the app. “RRate is also open source, so other people can look at the source code to better trust it or use the same methods in their own apps.”

The first two research papers about the app were published in 2014 and 2015. The second one compared RRate with the Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) Timer, a device developed by the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) and WHO. “The accuracy was similar, but ARI Timer requires community health workers to count breaths for a full minute, while RRate can be done within 10 seconds and provides visual cues to guide decision-making,” he says.

Since then, the app has been used for several global health studies in LMICs. In the study published in PLOS Global Public Health, BCCHR researchers analyzed thousands of measurements from a real-world setting, as the IGH partners in Uganda have been using the app to assess children with fast breathing arriving at their hospitals.

“As a data quality check, we collected two breathing rate measurements and they were very similar to each other,” says Dunsmuir.

Offered in several languages, the app uses more images than text, audio to mimic breathing noises, and vibration if the clinician is in a noisy setting. It also provides visual feedback indicating if the taps happened too fast or too slow compared to the average.

Through its various phases, this long-term project has also enabled IGH to train health-care workers in East Africa and a whole generation of researchers at BCCHR. “This type of work shows what the Research Institute is all about: a world-class training environment that strives to improve the lives of children,” Dr. Ansermino says. “Together, we have created an innovative way of measuring breathing rate and, now, we’ll work towards integrating it into clinical practice globally.”