October 6 is World Cerebral Palsy Day. There are more than 17 million people across the world living with cerebral palsy (CP). It is the most common physical disability in childhood.

Diagnosis Using Integrated Metabolomics And Genomics In Neurodevelopment (IMAGINE) is a research project at BC Children’s Hospital that is part of the CHILD-BRIGHT Network. CHILD-BRIGHT is a Canadian patient-oriented research network working to improve the futures of children and youth with brain-based developmental disabilities and their families. The network was recently awarded $3.75 million dollars from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

BC Children’s investigators Dr. Jan M. Friedman and Dr. Clara van Karnebeek are leading IMAGINE. Colleen Guimond is the project’s genetic counsellor.

What is the issue you are researching in IMAGINE?

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a non-progressive, but variable condition that affects one out of every 500 Canadians. CP is a term used to describe a group of disorders affecting body movement and muscle coordination. Brain injuries in early life are the cause of CP in many children. However, many children with CP have additional health issues, similarly affected family members, or other clues that the underlying cause of their CP may be genetic. These are the types of families who are enrolled in the IMAGINE study.

Many of the kids who are part of the IMAGINE study are followed very closely by the medical system and have many specialists involved in their care. In addition to CP, they may have symptoms as varied as seizures, autism, intellectual disability, or birth defects, but they don’t have an underlying diagnosis to tie their symptoms together. Now we know they may actually have an underlying change in one of their genes which can explain their set of features or clinical symptoms.

Advances in genomics and metabolomics have allowed us to better diagnose these metabolic and genetic causes of cerebral palsy. These insights will hopefully lead to more personalized treatments that improve the lives of these kids.

How are you doing this research?

There are 100 families now enrolled in IMAGINE and some families have more than one child taking part. Each child has two types of testing: genomic sequencing and metabolomic testing. The advanced level of genetic tests we do for the study are typically only available for research and are not available clinically.

We do whole genome sequencing where we look at the entire set of DNA instructions found in that child’s cells. We are looking for changes in the normal sequence of letters in the DNA, as well as sections of DNA that are flipped around, swapped, removed or added.

With metabolomic testing, we examine many proteins and enzymes that create patterns in our blood. Sometimes if a pattern is out of whack, that can give us a clue as to which area of DNA is affected, or it might point to a biomarker that indicates this protein is higher or lower in kids with these conditions.

I tell parents that we may find nothing. We may poke your child to get blood and still not have an answer for you. Or we may find a gene change that looks suspicious but has never been reported before, so then we need to follow-up. The genetic variation may have been noted in mice, but not in humans, which leads to the question: Is this a new diagnosis in the world?

With advances in technology, we are much better at finding genetic changes but understanding what that information means can take some work.

Sometimes families have to wait with uncertainty for a while because we find a variant of unknown significance. But as more studies get published, and we have more answers from other kids around the world, we can go back to that family later and provide them with a diagnosis.

What are you hoping to find out?

Cerebral palsy is a clinical diagnosis that would typically be made by a neurologist. We can be more specific about the cause of the child’s CP and other symptoms by coming up with a genetic diagnosis. We are looking for a unifying reason that the child has all those symptoms. CP may be a feature of that diagnosis. One little change in the way a particular gene functions, which alters the protein it’s supposed to make, can affect the way the brain develops.

We want to be able to tell families if a genetic change may have led to all these symptoms in your child. It doesn’t mean we are taking away the child’s diagnosis of CP, but we can provide an additional new diagnosis by way of an explanation.

Just over half the kids in the study have received a genetic diagnosis. We expect that number to increase as we go back and re-analyze the data with new information now available. We are very motivated to find answers for our families.

What have you already discovered?

IMAGINE was launched in April 2017 and there have been several papers published already.

There is an extensive overview of genetic and genomic studies on cerebral palsy and related neuromotor disorders. This publication shows that finding the cause of CP is essential to providing optimal treatment.

We have identified a biomarker for identifying some genetic causes of CP. A biomarker is a change in an enzyme level that is specific or related to a condition, and it allows us to make a diagnosis in a much faster, less expensive way compared to genomic sequencing.

Another publication looks at how advances in genetic testing for CP should also further the approach and guidelines for genetic counselling to support those families.

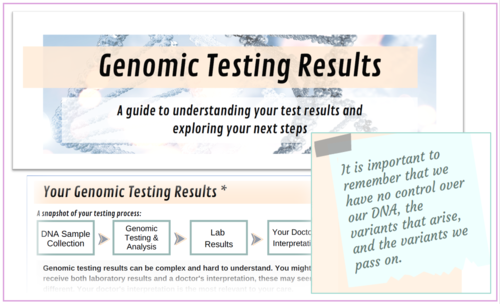

We created a patient and family-oriented resource to complement post-test genetic counselling, based upon feedback from our patient partners. The Genomic Results e-Booklet helps families understand their genomic testing results and navigate available resources.

How will this help children with cerebral palsy?

Having a diagnosis for these families means an end to a lot of tests. It means it could be the start of precision medicine. Maybe it changes a treatment for their seizures or other features. Maybe it means there is medication that may alleviate some features. Down the road, there may be a new therapy that could prevent new symptoms from appearing. A specific diagnosis is really the first step in being able to do all those things.

In addition, a diagnosis means we know the genetic mechanism behind their child’s symptoms. Is this a brand new genetic variant that was not inherited from the parents, which is called a de novo change? This is actually the case for a lot of families in IMAGINE. Or is the variant inherited from parents? If either case, we can provide more specific information if those parents are planning to have more children.

Families really value all these answers, especially the mothers who have been asked so many times, “During pregnancy, what medications were you taking, what exposures did you have, was the baby born early?” Parents often wonder if there was something they could have done differently that would have made things better for their child. Finding a genetic diagnosis presents a clear answer — the body is copying billions of letters every time a cell is made and sometimes there is an accidental change in the spelling of one of those genes.

We have also seen how empowering it has been for families to connect with others like them. The world is so much smaller now because of the internet. I have worked with families who have a child diagnosed with an extremely rare condition known to affect fewer than 20 kids around the world. Within days, they are connected with other families with the same diagnosis in Japan, Brazil, Germany, and so on. It’s such a special connection for these families.

We are adding more and more to the understanding of genetics. The more genes we are able to discover and the more rare conditions we can link to those genes, the easier it will be for other families in the future. They won’t have to wait years to get a diagnosis.