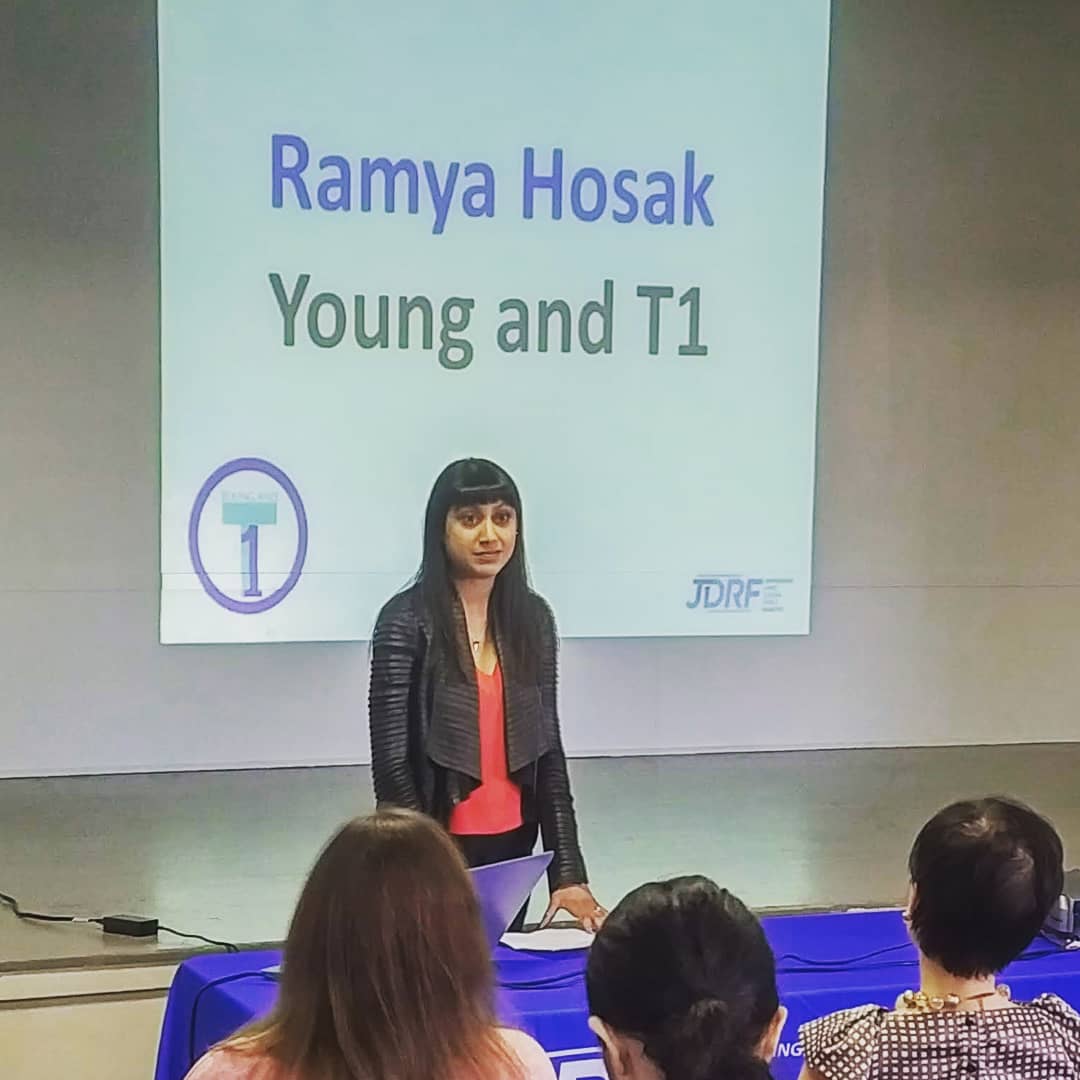

With a mom who is a cancer researcher, Ramya Hosak has grown up with a love of and interest in science. But it was her diagnosis of type 1 diabetes 15 years ago that really changed the entire trajectory of her life, once she got over the shock of facing a lifelong health condition. Hosak co-founded a support group for other young adults with type 1 diabetes, built a career in the health non-profit sector, and is now providing her patient expertise on a new diabetes research project at BC Children’s Hospital.

“I’m really passionate about being able to connect the researchers to patients," says Hosak.

"Researchers are giving their lives to their work, and it’s so much more meaningful when they can see who it is they are helping and learn more about what it’s like to live with diabetes."

Type 1 diabetes, or T1D, is an autoimmune disease that prevents the pancreas from making insulin. Insulin is an important hormone that regulates the amount of sugar in your blood. Without insulin, blood sugar levels can spike, leading to serious health problems or even death if not treated. People with T1D need insulin every day to live and be healthy. Previously known as juvenile diabetes and insulin-dependent diabetes, current data show that more than half of all new cases of type 1 diabetes occur in adults.

What immune cells 'eat' could provide answers to T1D

Dr. Bruce Verchere, researcher in the Childhood Diabetes Laboratories and Director of the Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics at BC Children’s Hospital, along with fellow researchers Dr. Megan Levings and Dr. Ramon Klein Geltink, are leading a $2 million study funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Levings is a world-leading immunologist and Dr. Klein Geltink is an expert in immunometabolism, an emerging field that examines the relationship between immune cells and the nutrients that fuel them. Together with their colleagues, the team is doing a deep dive into why the immune system attacks islet cells — the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin — and how metabolic pathways are involved.

“No one has looked at the immune cells that attack the islets to really try to understand what is happening between the two. We want to know if changes in how and what the immune cells 'eat' influence damage to the pancreas, and if they do, can we look at treatments that target these metabolic pathways,” explains Dr. Verchere.

Dr. Klein Geltink says it’s been over a century since metabolic pathways were first discovered, but now technology has caught up to be able to study them in a meaningful way.

“We can do things now in a few days that were impossible 20 years ago,” he adds.

“This allows us to study metabolites and metabolic pathways at a single-cell level and track interactions far more extensively for our research.”

Dr. Levings is working on how to “feed” immune cells different types of nutrients to develop new therapies for T1D.

“The concept of “you are what you eat” also applies to cells,” she remarks. “We think that changing the way we feed cells in the lab could help us create new types of cell-based therapies that could be used to stop or prevent autoimmunity.”

Taking the focus off a cure for diabetes

Up until now, much of diabetes research has been focused on finding a cure. For example, implanting insulin-producing cells grown from stem cells. But Dr. Verchere counters that those new cells don’t change the underlying autoimmune condition.

“We can only get to a real cure by getting to the fundamental reason why diabetes occurs.”

Hosak says that is precisely why she’s so excited about being involved with this project.

Since getting diagnosed with type 1 diabetes 15 years ago, Ramya Hosak has been told many times that a cure is coming. Yet it always seems to be another five years away.

Making patient concerns a priority in research

As part of her journey living with diabetes, Hosak looked for a community that would understand what she was going through. Trying to explain to her 20-something-year-old friends why she couldn’t just go out at 10 p.m. for a late night of drinking was a challenge. So she partnered with others to start a support group specifically for young adults living with T1D.

The group’s main goal is to provide a social network for people living with T1D during and after their transition from the pediatric system into adulthood. Increasingly, those patient voices are also advocating for research to reflect their concerns.

Dr. Verchere and the study team are listening. They consulted with patients while preparing the project proposal and made adjustments to address patient priorities, which included a focus on understanding how diabetes impacts women’s health, such as risks in pregnancy. Researchers are now differentiating between male and female cells as much as possible in each part of the project.

Hosak attends study meetings, provides feedback on the research methods and the language that is used in study documents, and guides the communication of results and knowledge translation.

“Spending time with people living with T1D makes you very aware of the impact of the work we are doing. We really want our research to be informed by the very people we are trying to help,” comments Dr. Verchere.