Researchers at BC Children’s Hospital and the University of British Columbia found that blood DHA levels are associated with cognitive performance in five-year-olds. More research is required to explain the surprisingly meagre association between DHA intake and blood DHA levels.

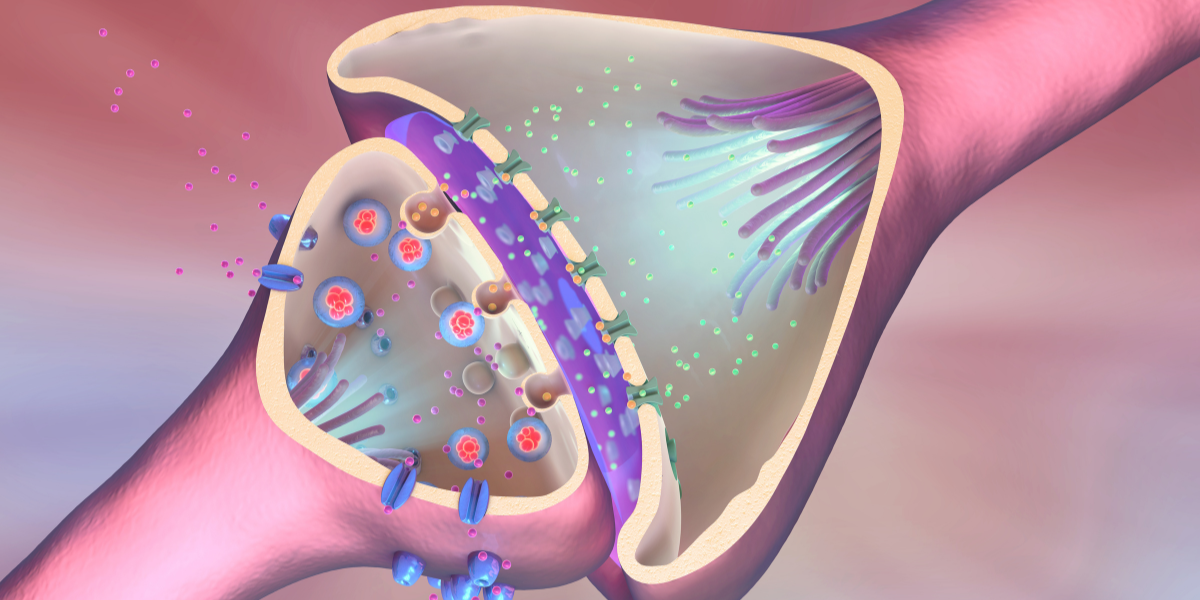

Early childhood is a period of rapid brain development, marked by an increase in synapses rich in an omega-3 fatty acid called docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). DHA comprises nearly a quarter of total brain-based fatty acids and begins accumulating in the fetal brain during the third trimester — a process that continues throughout infancy.

DHA is essential for healthy functioning of the brain, retina, and skin; and adequate DHA levels in the body may help prevent neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. DHA is involved in the transmission of signals between neurons as well as cellular responses to substances on or outside of the cell membrane. While DHA is vitally important for neurodevelopment, learning, and language acquisition, exact dietary DHA requirements remain unknown.

Dietary sources of DHA include aquatic organisms such as fish and shellfish, and small amounts of DHA are found in eggs and poultry. Another type of omega-3 fatty acid called alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) is found in flaxseeds, canola oil, tofu, pumpkin seeds, and walnuts. The human body can convert ALA into DHA, but this process is inefficient, does not produce much DHA, and can be hampered by modern Western diets high in omega-6 fatty acids.

While a balance between omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids is best, we tend to consume too much omega-6. Some products high in omega-6 include sunflower oil, soybean oil, and cottonseed oil — often used in processed and fast foods because they are inexpensive.

Dr. Rajavel Elango, Dr. Sheila Innis*, Dr. Kelly Mulder, and Roger Dyer assessed young children’s dietary DHA intake and blood DHA status and determined the association between these DHA levels and cognitive performance. The researchers used a series of standardized neurodevelopmental tests to measure the children’s short-term memory, visual processing, long-term memory, and attention.

Two groups of young participants took part in the team’s study:

- A cross-sectional group comprising 187 children aged five years and nine months, based in Vancouver, with no previous involvement in the team’s research, and

- A follow-up group comprising 98 children aged five years and nine months who had participated in the team’s previous study that looked at DHA supplementation during pregnancy.

Dr. Elango and his colleagues assessed each group’s dietary DHA intake by interviewing the children’s parents using a quantitative food-frequency questionnaire and then conducting nutrient analysis of foods and beverages consumed. Venous blood samples were also taken to measure the children’s blood DHA levels, and results from each group were compared. There were no significant differences between the two study groups.

“Interestingly, we found that dietary DHA intake was only moderately associated with blood DHA levels. In other words, high DHA intake through foods consumed doesn’t necessarily mean the child will have high blood DHA.” says Dr. Elango.

“There may be certain individual factors at play — such as genetic variation and fatty acid metabolism differences — influencing what happens to DHA in the body once it is consumed or synthesized.”

This finding also suggests that dietary DHA intake may not be the best marker for DHA status. Instead, researchers should consider using blood DHA to more accurately gauge participants’ DHA levels.

In terms of the neurodevelopmental results, blood DHA levels were positively associated with scores on some of the tests, while dietary DHA levels were only associated with the short-term memory test results.

“Long-term memory was not related to either dietary or blood DHA levels which is different from earlier animal model experiments,” explains Dr. Elango. “But it may be that the participants in both groups did not have low enough DHA levels to have negative impacts on learning or other cognitive outcomes.”

Read more in “Complexity of Understanding the Role of Dietary and Erythrocyte Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) on the Cognitive Performance of School-Age Children,” Current Developments in Nutrition.

Learn more about Dr. Rajavel Elango and his team at The Elango Lab microsite.

*Dr. Elango, Dr. Mulder, and Mr. Dyer wish to acknowledge the late Dr. Sheila Innis (1953-2016) for her dedication and important contributions to this research and to the field of lipids and childhood development.