BCCHR's Ask an Expert Series

We asked an expert about factors that can contribute to obesity during adolescence. While obesity poses serious health risks, there are many ways parents can support their teens in eating balanced diets and increasing physical activity.

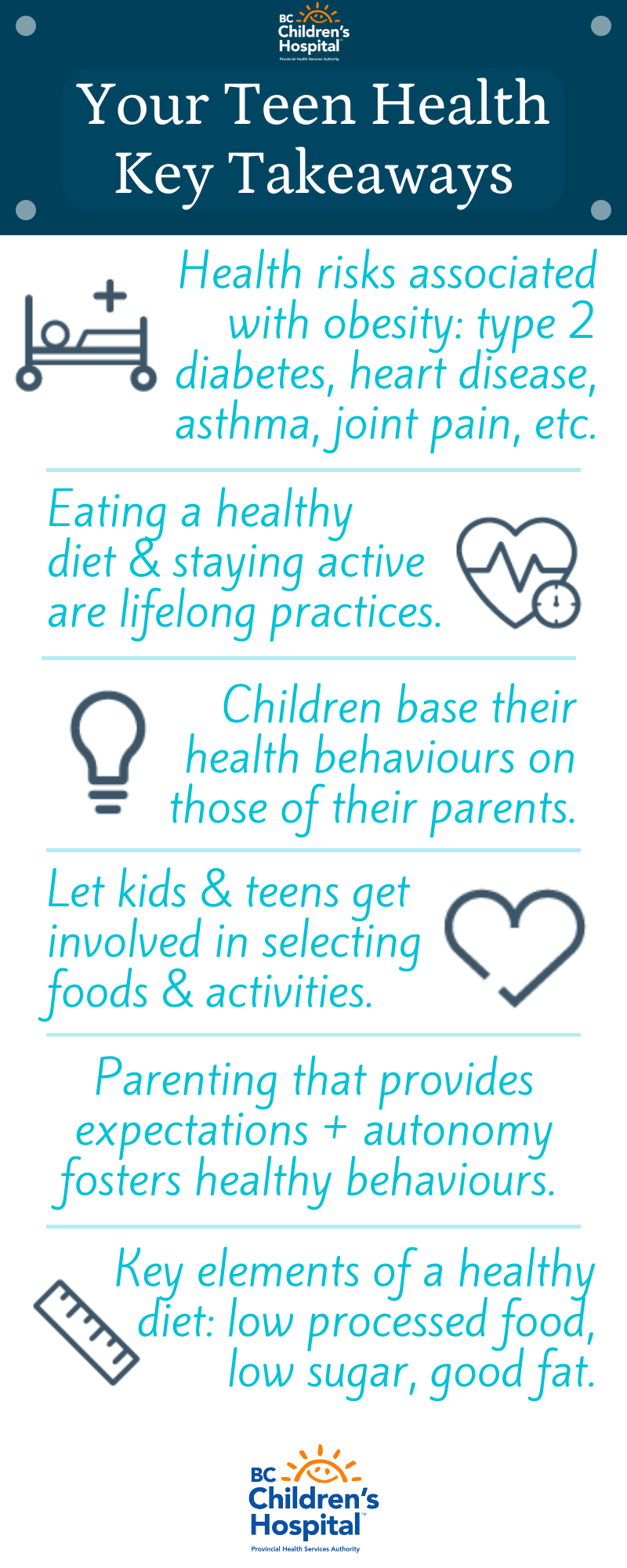

In Canada, obesity and overweight affect nearly 30 per cent of children aged 5-17. Health risks associated with obesity and overweight in this age group include type 2 diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, psychological issues (such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and behavioural disorders), asthma, sleep apnea, joint pain, and other conditions.

Dr. Louise Mâsse is an investigator at BC Children's Hospital whose research explores key aspects of children's lives that can lead to obesity. The ultimate aim of her work is to help improve interventions and treatments for young people affected by weight-related health problems. Dr. Mâsse was involved in the evaluation of Aim2Be, a "gamified" app for parents and kids 10 and up that helps with establishing easy and fun routines to improve health over the long-term.

We sat down with Dr. Mâsse to learn more about the ways that parents can best support their children in making healthy choices that last a lifetime.

What has been the main goal of your research?

I am most interested in answering the question: "How are young people motivated to sustain behaviour changes?" I'm interested in finding out what behaviour change techniques are most helpful when it comes to health interventions in teens. Right now, we have a good idea about which interventions work, but we don't always understand exactly why they work.

One of the greatest challenges when it comes to healthy eating and physical activity is adhering to new behaviours. We find that this is the hardest message to get across. For example, so many people think that they can just go on a diet, get the results they want, and then go back to what they used to eat. Moving to a healthy and balanced diet needs to be a permanent change. How to sustain this change is the tricky part.

Why do you think weight should not be the main focus when talking about adolescent health?

My colleagues and I would like to see the focus turn to establishing life-long healthy behaviours, because having what is referred to as "normal weight" does not guarantee that the individual has healthy behaviours. Also, there is evidence that you can gain some health benefits by adopting a healthy lifestyle — such as being active and eating well — even if you are overweight, and we cannot ignore that weight is in part genetically determined. This means that it is not realistic for everyone to achieve what is considered by the media to be an ideal body weight.

Your recent studies confirm that parental modeling is important in helping to establish healthy dietary and physical activity behaviours during childhood and adolescence. Can you explain parental modeling?

When a parent models particular behaviours — in this case, eating a healthy diet and maintaining adequate levels of physical activity — these behaviours serve as an example for the child, so the child bases their own behaviours on those of the parent. A child is more likely to enact the behaviours that they see and experience around them.

While parental modeling of healthy behaviours is important, we found additional factors that have strong impacts on children's health behaviours. Specifically, we found that certain parenting practices and parenting styles play key roles in the development of healthy eating and physical activity levels in children and teens.

Can you talk more about these parenting practices?

If parents simply model healthy behaviours and then let the child decide without setting clear expectations, that is not helpful for the child and does not often lead to sustained healthy behaviours. The goal is for parents to model healthy behaviours and set expectations that involve the child as a decision-maker.

Good parenting practices involve, for example, having discussions with your child about how much fruits and vegetables they should be eating for optimal health. One way to start the conversation is to show them what a healthy plate looks like so that they have a concrete mental image of what they're aiming for at each meal.

Then get your child or teen involved in selecting foods and planning physical activities. This can mean letting them help select nutritious foods for the family during shopping trips, choosing their vegetables at dinnertime, or deciding on a sport to play on the weekends. In doing these types of things, you've set clear expectations or guidelines for your child to follow and you've allowed them to be involved in making their own healthy choices.

Another important element of parenting practice is creating a supportive and encouraging environment around food and physical activity. This includes keeping the home stocked with healthy food choices, providing regular transportation to parks or community centres, and creating positive and fun routines that involve the whole family.

And what parenting style works best in helping to establish beneficial health behaviours in childhood and adolescence?

When we talk about parenting styles, typically we are referring to four main types: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved. Parents who practice authoritarian parenting are more controlling or restrictive and do not give their children much choice. They make many or most of the decisions for the child and most day-to-day activities are strictly regulated. The opposite of authoritarian parenting is permissive parenting where expectations, goals, and objectives are not communicated to the child, and the child is free to make most or all of their choices involving eating, screen time, and physical activity.

What we have consistently found is that authoritative parenting is best. A parent who is authoritative is what we refer to as autonomy supportive. These parents will communicate the kinds of clear expectations I discussed earlier and will involve the child in making choices within specific parameters. These parents are open to discussions, receptive to their child's input, and will consider modifying the parameters if necessary. In short, these are flexible but consistent parents who provide guidance.

Is there any specific diet that you have found works for establishing healthy eating in teens?

Comparing one diet to another is not usually very useful. A vegetarian diet, for example, is not necessarily healthier than a non-vegetarian diet. It could still have a lot of sugar or processed foods and a lot of fat.

No matter what type of diet you choose, there are some key elements that make it a healthy diet: low processed food, low sugar, and it should include healthy fats (unsaturated fats) in moderation and lots of fruits and vegetables.

A young person can reduce weight on a lot of diets, including a lot of the fad diets. The problem is that these diets are not easy to maintain because they are unrealistic, and some may even be harmful in the long-term. The diet has to be sustainable; if it's not sustainable, it's not healthy.

If you had one message to parents about this topic, what would it be?

Parents matter even as children move into and through adolescence. Parents often think that once their child is an adolescent that they have less of a role or that the child's peers now have more influence. While external influences do become stronger at this time, parental influence continues to matter. Parents continue to play a vital role in supporting and nurturing their child's health choices.

One stage to be especially mindful of is the transition between elementary school and secondary school. This seems to be a sensitive period in that it can trigger behaviours associated with obesity — lower quality nutrition, increased screen time, and increased sedentary behaviours. For example, we know that physical activity decreases by 60-75 per cent in adolescence and that the transition to secondary school triggers the beginning of the decline in physical activity in adolescents. Parents play an important role in helping to support nutritious choices and increased physical activity during this time.

I am currently involved in an epidemiological study looking at this transition and the interplay of influences related to the individual, their peers, family influences, and school changes.

***

Dr. Louise Mâsse's recent research articles about adolescent obesity and physical activity were coauthored with Dr. Mariana Brussoni and colleagues.

Resources for Parents

- Aim2Be: One small step at a time, your family will level up and discover tiny habits that will make you healthier and happier.

- Live 5-2-1-0: Several great resources to help inspire change in your family.

- ParticipACTION: Focused on changing behaviour through a movement for more movement!