The Silent Genomes project is a partnership between Indigenous organizations, Indigenous patients, and committed Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff with a variety of expertise, including medical doctors and geneticists. As part of our educational outreach, we would like to explain how genomic research is currently helping to manage the outbreak, and what it could mean to our project.

Last updated 21 June 2022

How COVID-19 impacts Indigenous Peoples and Communities

COVID-19 is a serious threat to our health. Like the flu, it is very contagious: the virus (a coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2) can spread easily and rapidly. As you are probably already aware, most people who are exposed to the virus will experience mild or even no symptoms. Although the virus can cause a severe case in anyone, those with chronic health conditions, or our elders, can be at higher risk and may have a higher chance of not surviving. In keeping with the Silent Genomes Project, this article will mainly refer to genomics in the fight against COVID-19. For clinical information, please refer to the links below.

Indigenous peoples have increased burdens of chronic heart and lung disease, which may make them more vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19. Moreover, many Indigenous people live far from centers that provide acute care, which makes it even more challenging to get necessary treatment.

The way we are managing this pandemic is ‘like trying to build a plane while flying it’. It is gratifying to see the whole world’s efforts to tackle this new virus from a genetic level up to human populations of millions. Scientists and health care practitioners are learning from one another on a daily basis. This includes those who work to ensure that Indigenous people have access to the best of healthcare, so that their voices are no longer silent.

The Silent Genomes team hopes this information provides you with a useful perspective on the coronavirus, how it may impact the lives of Indigenous Peoples, and how genomics can be used in the fight against COVID-19. Please contact us at silentgenomes@uvic.ca if you have questions, or wish to share information.

- What is a coronavirus?

-

Human coronaviruses are common and are typically associated with mild illnesses such as the common cold. COVID-19 is shorthand for Coronavirus Disease - 2019. It is a new disease that has not been previously identified in humans. There have been two other specific coronaviruses transmitted to North America, that have spread from animals to humans and which have caused severe illness: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in 2002 (caused by the SARS CoV virus) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2012 (related to MERS CoV virus).

Just like any living thing, a virus has genetic material (DNA or RNA), where it keeps all information about itself. Coronaviruses are RNA viruses, meaning their genetic information is RNA.

- SARS-CoV-2 variants

-

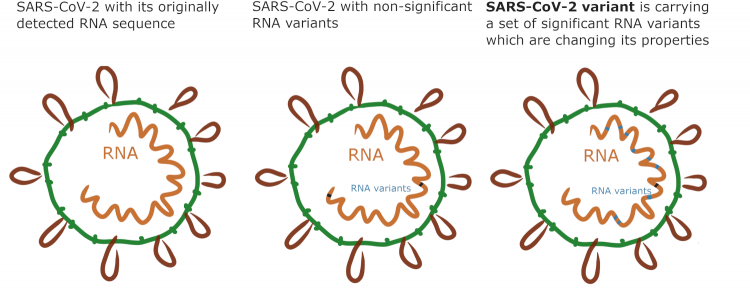

Each virus has its own characteristics, for example, they can lead to different illness, transmit in different ways, and the can change along the way! Although the SARS-CoV-2 genetic code is relatively stable it is still prone to mistakes (RNA variants), when making billions of copies in a human body. The mistake can increase or decrease how quickly the virus is spread, change the response to current vaccinations, etc. Scientists watch closely how these mistakes can affect the impact of the virus in humans. When the virus accumulates a specific group of RNA changes, it is called a "SARS-CoV-2 variant".

A few of those have recently drawn a lot of media attention, and these variants are often named for the region in which they are first detected (UK, South Africa, Brazil, India, etc), however, the most recent nomenclature names them after Greek letters (like "Gamma", or "Omicron"). For example, the variant named B.1.1.7, or Variant of Concern 202012/01, contains 17 meaningful changes and has been observed to spread more quickly. When situations like this occur public health efforts to limit contact with others to reduce the spread may be even stricter. It is important to note that if a variant reduces the response to a vaccination, our current technologies will allow the vaccine to be ‘tweaked’ to increase responsiveness again in a very short time!

Originally the goal for Canada was to sequence 5%-10% of SARS-CoV-2 viruses detected but sequencing efforts have now increased in order to control the spread of such variants. There are public health and research laboratories throughout Canada carrying out the sequencing.

- How can the genetic changes in the virus help with understanding where the virus came from?

-

RNA variants can be tracked to see where the virus came from in people who have had the virus (such as changes common to those who visited the US, Europe, or the middle East) and where it is spreading to. These changes in the RNA code assist in the public health efforts to trace the path of the virus.

- Can individual genetic variation decrease or increase our susceptibility to COVID-19?

-

Differences in human genes (DNA variants) may determine how sensitive an individual is to viral infection. This may be referred to as ‘host response’.

For example, genomic studies that were performed after the first outbreak of SARS in 2002 showed that some DNA variants in humans may alter the disease course. Some of these variants are related to a person’s vulnerability to acquire the disease, while others may relate to the immune response, meaning how certain cells are acting to fight the virus.

>Research into the role of human DNA variants in susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19 is underway. Although it may be early in the COVID-19 fight, scientists already seek to understand why some people might naturally be more resistant to the infection. Certain DNA variants may increase or decrease a person’s risk of developing COVID-19 or having a severe case. Efforts are now underway to detect such variants, to be able to predict the course of the disease in each patient or in a group of patients with that same genetic variant.

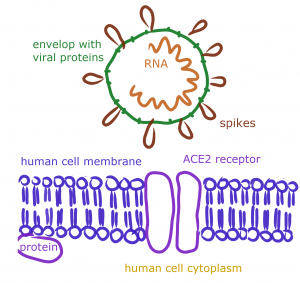

Figure 1. The ACE2 receptors are like the doors of our cells, which the RNA from the Coronavirus uses to enter and change the normal cell functions in the lungs, kidneys, heart, and gastrointestinal tract. For example:

[angiotensin converting enzyme 2] receptor, a structure that the virus interacts with to get inside of the cell. - It has been suggested that a gene cluster related to the ABO blood-group system is related to a genetic susceptibility site in patients with severe COVID-19 infection experiencing respiratory failure. However follow-up studies have not supported this hypothesis.

- Another study suggests that variants of the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) system which it responsible for the regulation of the immune system, may impact the susceptibility to and severity of the infection.

- A number of other potentially involved human genes have been suggested or reported.

To date, there is still not enough scientific evidence to confirm or reject these preliminary findings. More certain results will be obtained from organized and logical approaches (e.g. repeating the studies with more individuals) and from the application of advanced genomic methods (Whole Genome Sequencing). This might help us to identify who is at risk in our society and where more safety precautions are needed.

COVID Human Genetic Effort. - Can the IBVL be helpful in the fight against COVID-19?

-

The proposed Silent Genomes Indigenous Background Variant Library (IBVL) will be a database showing the frequency of DNA variants found in Indigenous people (without known genetic conditions). It is important that a diversity of populations are represented in background variant libraries, since variants not seen at all in one group of people may be very common in another. Please read more about the IBVL on our IBVL webpage. Whole Genome Sequencing allows identification of many thousands of DNA variants which can help identify variants which decrease or increase our susceptibility to COVID-19.

There are already a few projects around the world, and some planned in Canada, which are focused on the analysis of genomic data from people who had different responses to COVID-19. Understanding the genetic factors for why some people experience more severe COVID-19 symptoms than others, can improve treatment and vaccine development. The IBVL could help in these types of studies, because the background variants that are present in Indigenous peoples may be absent in other population databases.

The IBVL that is being developed as part of the Silent Genomes Project could provide the ‘reference’ data important in the understanding and sequencing of Indigenous patients with COVID-19 who have consented to having their genomes explored. The use of the IBVL for this purpose, will be decided upon by the Indigenous-led IBVL Steering/Governance Committee.

- How is genomic technology used to identify viruses?

-

Genomic technologies were used to read and analyze the RNA sequence of the virus. Knowing the viral RNA code has allowed direct testing for COVID-19 and distinguishes it from other viruses.

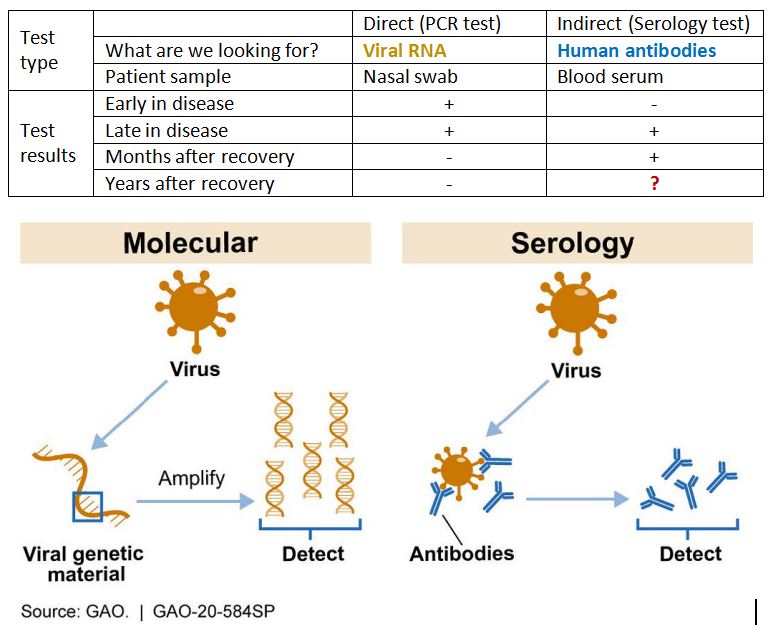

Direct Diagnosis. You may have seen images of people having a nasal swab to test for COVID-19. The genetic technology called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is used for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Genetic testing is considered a direct and accurate method, since it can search specifically for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a patient's test sample - no other virus will give a positive test result. After recovery, viral RNA will not be detectable in a patient's sample.

Indirect Diagnosis. There are non-genetic (serology) tests that can also help with the diagnosis of COVID-19, especially for those who are several days into the illness, or may have had the virus without knowing it. These tests are indirect because they look for signs called antibodies which our immune system develops upon the first contact with the virus. Antibody testing may be less specific than genetic testing as it assesses the body’s immune response in the presence of the virus rather than detecting the virus itself. In addition, this test will stay positive after the patient’s recovery, which could point to longer immune defense against this virus. However, much remains to be learned before we can tell how long natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 lasts.

However, one must keep in mind that some margin of error exists in the testing for COVID-19. Read more on the BC CDC website.

- How else can genomic technology help in the fight against COVID-19?

-

Genomic technology can also answer many other types of questions about the virus and the human response to it. Of particular interest, genomic studies have highlighted the value and importance of transparent data sharing across countries, which enables live tracking of the spread of COVID-19. In addition, a number of projects around the world (e.g."COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative", or “Genomics of COVID-19: molecular mechanisms going from susceptibility to severity of the disease”) are aiming to combine efforts in the fight against the virus. In Canada, an emerging project called CanCOVID, our country’s expert-led response to the Coronavirus, including two Indigenous advisors, Dr. Jeff Reading and Sharon Edmunds, who are also both advisors to the Silent Genomes Project.

Some treatments are slowly becoming available for SARS-CoV-2 in Canada (for example the antiviral medications called Remdesivir and Veklury, please refer to Health Canada for current information).

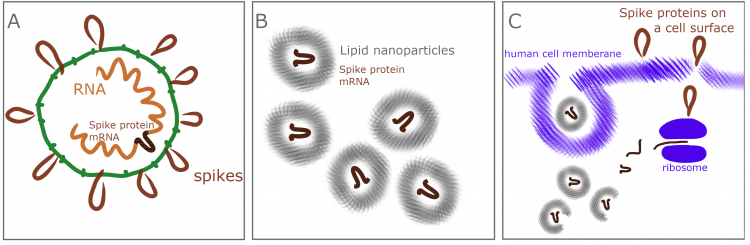

Importantly, tremendous worldwide efforts have resulted in vaccine development, including gene-based vaccines which have not been used before (mRNA vaccines).

- Vaccine development around the globe

-

In the past, vaccine development could take up to 15 years! The unprecedentedly fast development of the COVID-19 vaccines became possible due to several factors which include:

- previous research on Coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, which started in 2002, described this relatively new type of respiratory failure syndrome and provided a basic knowledge of Coronaviruses,>

- The policy of open access to COVID-19-related publications for research communities around the globe, and generous funding of COVID-19-related research,

- Advances in genomic technology have made it possible to determine the sequences of the entire genomes, classify them, and collect them in databases for research access (genomics); to copy or create novel DNA and RNA sequences in the lab and to insert them to different organisms (genetic engineering, gene therapy).

Within the last six months, laboratories around the world have developed more than 160 vaccine candidates in the fight against COVID-19, with more than 20 having entered different phases of clinical trials. Below is a description of the major types of candidate vaccines:

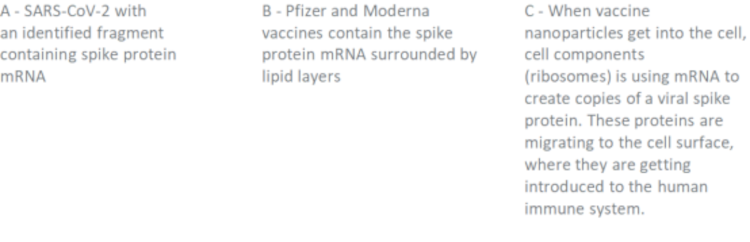

- Nucleic acid-based vaccine - this group includes mRNA vaccines and DNA vaccines. Nucleic acid vaccines are not introducing viral proteins into the body - in the case of mRNA vaccine, the human body is making a protein resembling the viral one, preparing the immune system to fight against the real virus. Pfizer and Moderna vaccines approved to use in Canada both are mRNA vaccines.

- Recombinant viral vectored vaccine - these vaccines are live viruses (but not Coronaviruses!) that are safe for humans and are instructed to produce non-dangerous SARS-CoV-2 protein to get them introduced to the human immune system. Vaccines of this type created by AstraZeneca and Janssen (Johnson&Johnson) have been approved for use in Canada.

- Sub-unit vaccine - these vaccines use only specific pieces of the viral proteins. Virus-like particles are also a type of subunit vaccine and are molecules that closely resemble viruses, but are non-infectious because they contain no viral genetic material.

- Live attenuated vaccine - these vaccines use a live but weakened form of the virus.

- Inactivated virus vaccine- or “killed vaccine” is a vaccine consisting of virus particles, which have lost their capacity to produce disease.

More information about candidate vaccines are available in scientific reviews (Jeyanathan et al., 2020, Kaur and Gupta, 2020) and reader-friendly articles (The New York Times, Nature News Feature). It is important to note that even though the vaccinations are being produced quickly that strict criteria for approval must be followed by regulatory agencies such as Health Canada before they are released for public use.

- Vaccines in Canada

-

The Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine, have been approved for use by Health Canada and have been available since December 2020 (Canada, BC). Both are the newest generation nucleic acid-based vaccines (mRNA vaccines). AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, Covishield, and Janssen (Johnson&Johnson) recombinant viral vaccines have been available since the end of February and March 2021. To find the current list of approved vaccines, consult with Health Canada.

To find information about receiving your first, second, or additional booster doses, refer to the provincial Get Vaccinated system to register online or by phone. Help is available in 140+ languages.

Below, are several videos that further describe vaccines development process and how they work in our body.

Government of Canada (video, Dec 2020) COVID-19: How vaccines are developed

Science Journal (Video Jan. 29, 2021) How do the leading COVID-19 vaccines work? Science explains

Simply explained (Youtube video, Dec 2020) How mRNA Vaccines Work

Achievements and challenges

If you would like to learn more about COVID-19 symptoms, the current state of the pandemic globally and in Canada, and current research on these topics, please refer to these links:

More about COVID-19 Management

- Symptoms of COVID-19

- General FAQs(where to get the vaccine, transmission, self-isolation, mask-wearing, etc)

- Translated content about COVID-19 from BCCDC

- COVID-19 information in K-12 schools and child-care communities

Current state of the pandemic globally

- COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative

- World Health Organization: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Myth busters

- Nextstrain

Current state of the pandemic in Canada

- COVID-19: Indigenous awareness resources

- Health Canada Info and Daily Updates

- Health Canada COVID-19 Outbreak Update

- CanCOVID

- COVID-19 Immunity Task Force

- COVID-19 Resources Canada

- CBC News: COVID-19 page

-

- British Columbia

-

Resources from Indigenous and public health organizations in Canada

Last updated 20 Mar 2025

The intent is to show how Indigenous Peoples are demonstrating sovereignty, self-sufficiency, community empowerment, and involvement. These sites listed below are good places to start your search and offer a number of other links to answer your basic questions.

Post-Pandemic Mental Health: Data and Resources

Government of Canada: Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Indigenous communities

Assembly of First Nations: COVID‐19 Information in Indigenous Languages

First Nations Health Authority (British Columbia)

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami: COVID-19 Tool for kids, Nunavut enacts strictest travel regulations in Canada

Aboriginal Peoples Television Network: National News on COVID-19

First Nations Health Managers Association COVID-19 page

International Indigenous Resources

New Zealand

Māori COVID-19 | Te Rōpū Whakakaupapa Urutā

New Zealand Maori Council: COVID-19 Guidance for Maori and Maori communities/organisations

Australia

The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales: COVID-19 outbreak page

United States

Urban Indian Health Institute: COVID-19 Updates and Resources

Navajo Department of Health:

Being in this together is a part of Good Medicine. To learn how other Indigenous peoples are helping each other get through this:

Indigenous health today (article, May 07, 2020) Tips and Tricks by Youth for Youth – FNHA

Indian Country today (article, September 12, 2020) Navajo Nation takes part in COVID vaccine study

- Earlier publications

-

The Tyee (article, 30 March 2020) On BC's Coast, Indigenous Communities are Locking Down

APTN News (video, 20 March 2020): More jingle dress dancers join in to share healing and joy

Facebook video: Singing with Keysa Parker and Waayenta Longboat

G-ZYFTS19B87